The Sulla Collection: A Lifelong Quest Preserving the Artifacts and Memory of the Italian Campaign

An Italian collector’s lifelong mission to save the stories, objects, and humanity of those who liberated his homeland.

As part of our ongoing series highlighting members of the international community supporting The Allies Museum: World War II Liberation of Italy, Founding Director Guido Molinari sat down with Giovanni Sulla, artifact collector and founder of The Sulla Foundation. For more than forty years, Sulla has dedicated his life to recovering, preserving, and interpreting the material history of the Italian Campaign. His extraordinary collection, now pledged to The Allies Museum, stands as one of the most comprehensive assemblies of Allied and Axis artifacts in Italy, with a special focus on the American and Brazilian forces that fought on the Gothic Line.

Giovanni, you’ve been collecting World War II artifacts for over forty years. When and how did you start?

It all began thanks to a commemorative initiative at my elementary school in Montese in 1975, organized by the headmaster for the 30th anniversary of the end of the war.

He had been the leader of a partisan formation during the conflict. I was nine years old and was deeply impressed that even veterans of the First World War, survivors of the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, also participated. They must have been between seventy and ninety years old. In the school gym, an exhibition of wartime materials was set up. There were tons of items. Local farmers brought in everything they had found over the years.

At the end of the exhibition, instead of asking my mother to buy me toys like Play-Doh, I asked her to buy some of the items from the display, which otherwise probably would have been lost. I remember she spent 100,000 lire (about 700 dollars today).

My passion was born because I used to read war and superhero comics. Every house in Montese had something left from the war, since the front had stayed there for six months during the winter of 1945. We’re right on the Gothic Line. People still remember both the good done by the Allied soldiers, the Brazilians and Americans, and the harm done by the Germans; we’re near Marzabotto, after all.

Everyone had military objects at home. Children went to school with wartime backpacks. Farmers wore camouflage jackets from the war; they even went hunting in those waterproof WWII military coats.

There weren’t many books to study the topic back then. In the 1980s and 1990s, the first veterans of the 10th Mountain Division began to return to Montese to see the places where they had fought. I started going to Prato, where one could find many things, and also to the American market in Livorno. There were crates full of gear, even Boy Scout boxes overflowing with stuff.

My goal has always been to save history. I was one of the first people in Italy to own a metal detector. I would roam around Monte della Torraccia and find all sorts of things, even dog tags of fallen soldiers. I even found three German soldiers who were later given a proper burial at the German military cemetery at the Futa Pass.

You have one of the largest, if not the largest, collections of American artifacts related to the Italian Campaign. Could you tell us about three objects you’re particularly proud of?

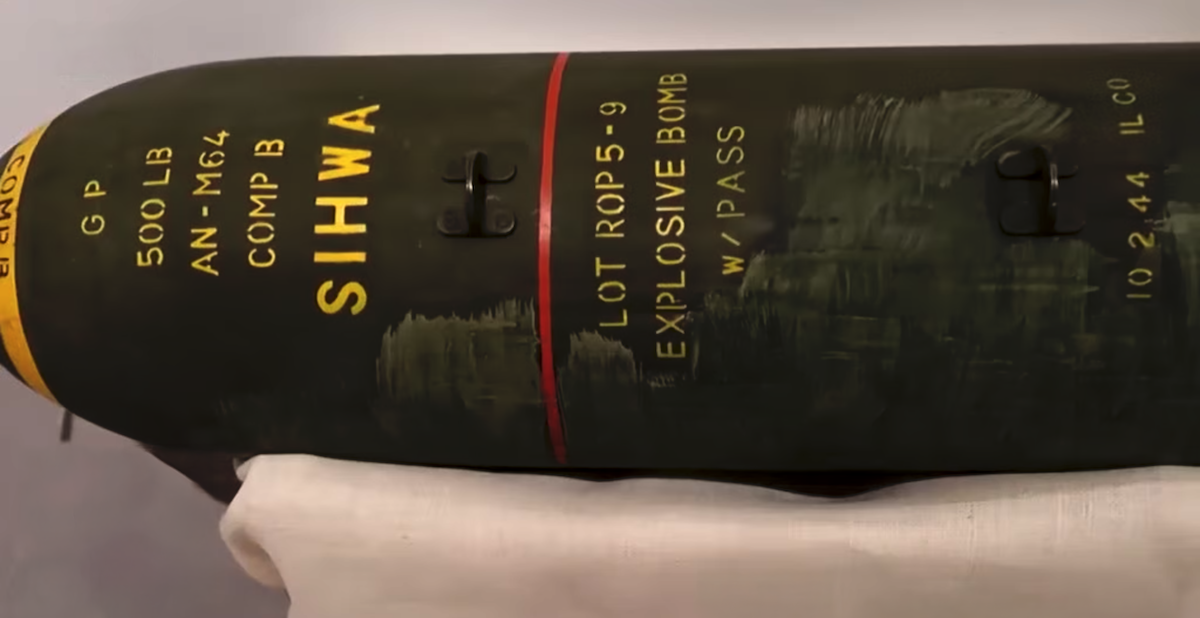

The most meaningful items aren’t the bombs; they’re the personal belongings. I’m a hunter of the daily life of the Allied soldier in the trenches. Dog tags are the most moving of all. I recently bought some original American chewing gum from the period.

I also collect documents, every paper I can find from the Italian front. Over time I’ve specialized. For example, I’m not interested in a German U-boat; I focus only on Allied and German units that fought in Italy. Among the Allies, mostly the American and Brazilian troops who fought here, among the thirty-eight nations that took part in the Italian Campaign.

The best things are those with names, which allow me to do research. I consider myself lucky to have turned my passion into my work. I’ve been to Normandy and Belgium, and I’ve worked with many museums both in Italy and abroad.

Perhaps my three most treasured are a dug-up helmet with both entry and exit holes, a Purple Heart given to me by a veteran on Monte della Torraccia, and something cheerful that evokes America, a Coca-Cola bottle brought to Italy by American soldiers, still full. Another favorite is a baseball bat signed by Joe DiMaggio.

American artifacts, in particular, show the cultural, economic, and industrial power of the Allied armies.

You also have a vast collection of Brazilian artifacts. How did that interest begin, and could you tell us about one item from that collection?

The caretaker of the Brazilian military cemetery in Pistoia, Miguel Pereira, was the first to teach me about the Brazilian contribution.

Among the many items, I have a 1943 poster by Vargas depicting a Brazilian and an American soldier embracing.

Another very touching piece is a blood-stained stretcher found in a field hospital.

Beyond the objects, there are also the stories. Fifty-eight Brazilian soldiers married Italian women. There were hundreds of marriages between Allied veterans and Italian women.

In what other occasions and places has the public been able to see pieces from your collection?

I’ve collaborated with the Ansaloni family’s Museo Memoriale della Libertà in Bologna. I’ve done six exhibitions at the Brazilian Embassy in Rome. I’ve worked with various museums in Brazil. I’ve shown artifacts at the Nembo barracks in Pistoia, and at the local museums of Zocca and Montese, where in the castle there are 850 pieces from my collection, including the only Allied military altar, that of Father Antonio Silvestri. Other museums I’ve collaborated with include the Winterline Museum in Venafro, the Museum of the Po Valley at Sermide, and the MuGoT, Museo della Linea Gotica in Scarperia e San Piero. People sometimes ask me why I don’t donate my collection to one of these institutions. It’s because I want the material to stay together, to find a place that values it and showcases its uniqueness.

We are deeply honored that your collection will become a cornerstone of our future public collection in Rome at The Allies Museum. Why do you think it’s important for the public, and especially young people, to have access to these artifacts?

We’ve reached a point in world history where peace and the end of war’s suffering are taken for granted. But given what’s happening today, we need to remind young people what war really was.

Eighty years ago, young men from all over the world came to Italy, not to conquer us, but to give us freedom and democracy.

As Italians, we must remember that we signed an unconditional surrender to the Allies; they could have done whatever they wanted with us, even left us a nation of shepherds and illiterates, as Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. advised. But that didn’t happen.

Thanks to the Marshall Plan, by 1950 the Italian economy was stronger than in 1939, and by the mid-1950s came the economic boom. So much American material was left here that both children and grandparents can connect to it: the child who sees the Coca-Cola bottle, and the grandfather who once received one from an American soldier. Many elderly people who were children during the war have told me that chocolate is everywhere now, but when they first tasted it at eight years old, given by an American soldier, it was the most delicious thing they had ever eaten.

Why don’t we have a museum in Italy comparable to those in other countries?

Many Italians still feel sorrow, thinking that we lost the war. I wouldn’t go so far as to say we won it with the partisans or the co-belligerent forces, but we tied it, in a sense.

It’s a pity there are no great museums, not in Anzio, not in Cassino. I went to Belgium to tour the Ardennes; in Bastogne there’s not much there, except that a great American battle took place. In Normandy, one of France’s poorest regions, they’ve made cows and bunkers into tourist attractions, and there are always people there. I go every year.

In Italy, many descendants, for example, about a hundred grandchildren of the 10th Mountain Division veterans, have recently come to visit, but they don’t find much here.

For schools, I’ve taken many students around; young people love comparisons. Seeing a rifle twisted by an explosion says more than a general’s jacket with medals. People want to see the real object, something used.

We have a huge opportunity in Italy. We have the Colosseum, and just an hour from Rome is Anzio; forty minutes from Florence is the Gothic Line. We shouldn’t glorify war, but by showing war we can help avoid repeating past mistakes.

Editor’s Note: This interview was conducted by Guido Molinari with Giovanni Sulla on November 4, 2025.